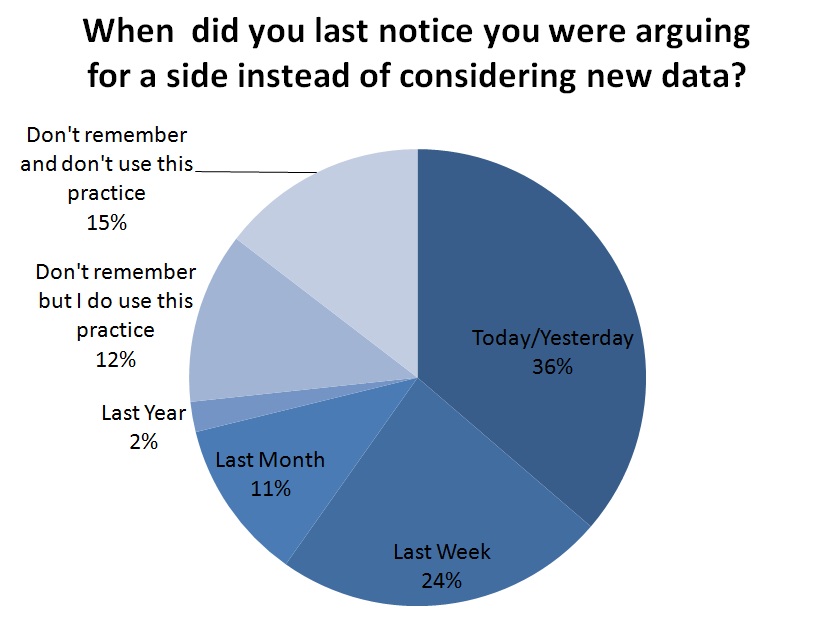

When you filled out our survey on the Rationality Checklist, most of the habits we asked you about in the first installment were about noticing. Noticing you're falling into a bad epistemological habit is useful data; it means you have the opportunity to intervene. So, we asked you about a bias that, if unchecked, screens you off from considering new information:

I notice when my mind is arguing for a side (instead of evaluating which side to choose), and flag this as an error mode. (Example: Noticed myself explaining to myself why outsourcing my clothes shopping does make sense, rather than evaluating whether to do it.)

We'd list triggers for this kind of thinking, but we'd end up going on and on: any time you're in an argument, when you are reconsidering a decision, when you look at data that's related to something that touches your identity, etc. Small wonder that nearly a third of respondents had caught themselves doing this one to two days before taking the survey.

The first step is noticing you're not really listening to the data, but what then? Several of you had stories to share about how you adjusted once you caught yourself out.

I decided recently to replace my old slate roof with a new slate roof, despite the high cost of that material. I asked a friend who was a realtor if she'd noticed that houses with slate roofs are easier to sell, or have higher resale value, ostensibly to help me make the decision of what kind of roof to buy (I had in mind subtracting the discounted future increment to the house's resale value from the current premium cost of the slate, as one component of the decision problem). While she was answering, though, I remembered that I'd already made the decision to go with slate, and therefore was only seeking confirmation of what I already believed. I recognized this as irrational, and that realization led me to reexamine why I wanted to spend the extra money.

Sometimes, pausing to wonder why you're reluctant to hear new evidence can help you notice information you weren't consciously factoring into your decision:

I spent last week trying to decide on a smartphone plan to replace my previous, voice-only plan. I spent several days comparing prices, and realized that my brain kept trying to argue for my current company even though it wasn't the best price. I examined my reasons more carefully, and realized that there really were factors in the decision that were important to me other than money--company ethics, my personal experience with each company, and quality of customer support, specifically. I did end up choosing to stay with my current company, but count this as an example of #3 since noticing allowed me to evaluate based on the factors I really did value, rather than either unexamined factors or unexamined bias. My brain isn't always wrong, but I like to know what it's really doing. [emphasis added]"

Rationality isn't about overruling or radically overhauling your brain. It's about getting a better sense of how it works so you can confidently rely on it to do what it does best and be a little more deliberate and careful when you know you're in a blind spot. For example, in the class we teach at workshops on the Fight/Flight/Freeze response the goal is to be able to notice why you're getting skittish but to use the tools we teach to act on that data in a less panicky way.

Check out all the results and stories from out Rationality Checklist survey by browsing the ‘Rationality Checklist’ category