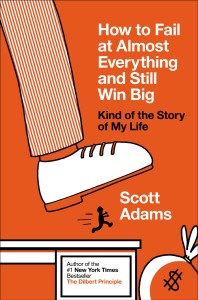

Scott Adams may be best known for the comic strip Dilbert, but he's also an entrepreneur many times over. He'll be the first to cheerfully admit that most of those businesses failed -- and to turn those failures into some very thoughtful insights about success and rationality. I checked out Scott's latest book, "How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big," after hearing enthusiastic recommendations from many CFAR alumni (as well as some CFAR staff), and called Scott last week to talk to him about it. Our conversation's below:

Julia: There's so much about your book that really resonated with what we teach at CFAR. Like the idea that we’re “moist robots” and we can learn to reprogram ourselves, to some extent. And of course, all the stuff about the fallibility of our judgment. And about looking for overlapping sources of evidence -- not relying solely on your own personal experience, but cross-checking it with expert advice or scientific studies.

So my first question is: Clearly expert advice and scientific studies can be very valuable sources of evidence. But within those categories, there’s a lot of variability, right? Do you have any guidelines for deciding how much trust to put in a given expert or study?

Scott: I can’t say that I’ve ever tried to catalogue that, in the sense of having a rule. But in general, when experts are dealing with some big unfathomable future, and it’s a complex system, I tend to discount that. The complexity makes it almost impossible to predict.

Also, if they are using a model, I pretty much discount everything I hear. But if they are just looking at data like a scientist and saying, “When this happens, that happens,” then I’m going to put more stock in it.

And then, what is their financial incentive? If they wanted to make a recommendation that was outside the norm for their industry, what impact would that have on their career?

Julia: OK, let’s take an example. How about expert advice about business?

Scott: The jargon, buzzwords, ideas about business management and success -- they all seem to have the same quality. Which is: whoever first came up with the idea looked at some places it made perfect sense, and then imagined therefore it could be generalized to other completely different situations. That tends to fail almost all the time.

The other thing that always amuses me about management truisms is that it’s so easy to make a case for the exact opposite.

Julia: Yeah, that’s a great mental test, isn’t it?

Scott: Yeah. For example, when people talk about how "passion" is responsible for their success... Flip it around and ask, “What else could they have said that wouldn’t make them sound like jerks?’ Even if they think the answer is that they are just smarter than people who don’t have money, they can’t say that. They can’t say they were just lucky because that ruins the mystique. They can’t say they do insider trading, if they did. There’s almost nothing they can say that doesn’t make them sound like jerks.

Passion is just the politically correct, easiest thing to put out there because it makes it feel as though people who are not successful could just generate a little extra passion and things would work out. It makes it look like other people’s fault without actually saying that.

Julia: That’s actually a nice application of Bayes’ Rule – do you know it?

Scott: I run into it all the time and then I get bored and I don’t look at it. What does it say?

Julia: It’s a theorem about how to evaluate evidence. The question you ask yourself is: how much more likely would I be to see this evidence in a world where hypothesis X is true, versus a world where hypothesis Y is true? And the more lopsided that ratio is, the stronger the evidence is for one hypothesis over the other.

So you ask, “How much more likely would I be to hear people saying passion is responsible for their success, in a world where that’s true, compared to a world where it’s not?” Not much more likely, as you pointed out, so that's pretty weak evidence.

Scott: Right. I guess that’s pretty intuitive.

Julia: Yeah. I mean, it’s not obviously intuitive when you first see Bayes’ Rule written out as a theorem, but after a while, it is.

Scott: This didn’t make it into the book, but a friend of mine read that part about passion, and said, “You know I’m not buying that. Look at the winners on American Idol, those guys clearly have passion for singing and that has to make a big difference,” and then I said, “Have you seen the first few episodes of American Idol? Every season there’s a stadium full of screaming, passionate people who don’t get past the first round. Going by the numbers, passion is probably far more associated with failing than success.”

Julia: Right. It’s kind of the wrong conditional probability, looking at the probability of passion given success, as opposed to the probability of success given passion.

Scott: Yeah.

Julia: Your systems-versus-goals argument was one of my favorite parts of the book. [Scott argues that following a system, like “Eating right” is better than pursuing a goal, like “Lose 10 pounds.”]

Do you think people have any trouble staying motivated to follow these systems? I mean, if they’re not focused regularly on the goal that justified that system in the first place, is it difficult to stick to?

Scott: Good question. It’s premature for me to have that kind of feedback yet because people have only had the book in their hand for a few months. The whole systems-versus-goals thing was something born out of my own life and my observations. I’m not regularly observing others and how they are doing with their systems.

Part of the problem is, with a system you don’t have a [specific success condition] like “I will do this on Tuesday.” It’s just that your odds will improve in some way you can’t identify today. So you don’t know if the system is working, or will ever work at any given point. It might take a while.

Julia: I was also intrigued by your story of how the doctors diagnosed you with focal dystonia [a neurological condition paralyzing Scott’s hand muscles during certain activities, like drawing]. They told you that basically no one recovered from it. But you resolved to be the first -- and you actually succeeded.

That’s obviously a very inspiring story. But ignoring the odds can also be dangerous, right? Like, if you hear that no one has ever survived jumping off the top of the Empire State Building and you resolve to be the first… Of course, that’s a straw man example, but do you have any advice on when you should ignore the odds, and when you shouldn’t?

Scott: In the case where ignoring the odds isn’t a big risk, and you’ve got the time and the resources to experiment... I guess the question is just, how big is the downside? If you’re thinking about jumping off a building, maybe you wait around and see if some other option presents itself before you jump.

Julia: Right. Also, it sounds like the disorder wasn’t that well understood, and it was at least somewhat plausible that it could be overcome. As opposed to, you know, we understand the physics of jumping off buildings pretty well.

Scott: Yeah, what was interesting about focal dystonia is that it was identified as a brain problem and not a physical hand problem, and given that there’s plenty of evidence of neuroplasticity, it was reasonable to assume that there was some rewiring possibility there.

Julia: I was intrigued by your examples of what you call “practical illusions” – things that are motivating even if you don’t have a good, logical reason to hold those beliefs.

Part of the problem for me is just, how do I suspend my beliefs? How do I convince myself on a deep enough level that, say, people actually find me charming, if I think I have good reason to doubt that? Are you able to just do that automatically?

Scott: No. I’d say it’s a human ability to hold two competing thoughts at the same time. So at the same time as I’m saying, “Damn, I’m good at X,” there’s a voice saying, “You know, you haven’t really looked at the data, that time it worked could have been luck.” I hear it just as loudly, but I can focus on one more than I can focus on the other.

Julia: Do you think there could be any risks? Could this make you more susceptible to being in denial about realities you actually should face?

Scott: I think the practical illusion is only good when you are aware that it’s potentially an illusion. I think you can tell yourself “I’m going to beat this tennis opponent,” and that doesn’t need to be literally true. It’s far from telling yourself, “I think my business will work despite the fact that I've been open for ten years and not one person has bought my product.”

Julia: I really liked the list you had the other day on your blog, of things that you’d changed your mind about in each decade of your life. Were you emotionally invested in any of those beliefs, in a way that was preventing you from changing your mind sooner?

Scott: It did take some time to get myself out of the mindset that I could pick stocks better than world experts at stock-picking. Your ego says, “Against the world of people who invest, if I’m one of the smarter ones, I should do better than the average.” It just seemed that I should be able to beat those odds -- but you eventually learn that’s a fool’s errand.

Julia: I have one last question for you. You say in the book that maximizing your own total happiness is the only goal that makes sense.

But, for me at least, there are many cases in which I can decide whether or not to face the problems that exist in the world. If I do, it’ll depress me, and maybe I can do something about those problems, but I certainly can’t fix them entirely. Or I could decide to not focus on those problems, and I would be probably happier, but I would be doing less good for the world.

So would you say it doesn't make sense to choose the first path?

Scott: The economist in me says: if you didn’t spend your half-day at the soup kitchen and instead worked a little harder to improve your income, because you're selfish, you are going to pay more taxes. And those taxes go to more good things than bad, even though we all like to hate the government.

Taking care of yourself is really an unselfish thing to do in the sense that it removes the need for other people to take care of you. If you don’t take care of yourself, other people are going to do it. They are not going to let you just die in the ditch. So this whole idea that these acts are selfish and those are unselfish is, I think, misconstrued.

Julia: Okay, thank you, Scott! It’s been a pleasure.

Whether you're a CFAR alumnus or just curious about rationality and why it's useful, I predict you'll enjoy Scott's book. Pick up a copy of "How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big" here and check out his blog too.